Asynchronous operations are impossible to avoid in almost every modern application. Each time you interact with network, database, filesystem or UI, some asynchronous operation is involved. iOS provides many mechanisms to provide asynchronousness including GCD and NSOperationQueue and encourages design patterns like delegate and callbacks that promotes asynchronousness. Unfortunatelly writing asynchronouse code in Swift is not always very clean, especially when implementing more complex chains of operations.

Let us imagine the following scenario:

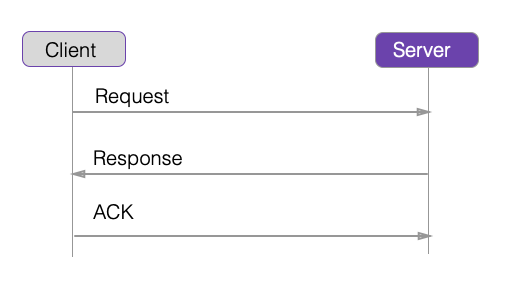

Some client sends a request to a server, which responds with a message, which then is confirmed by the client by sending ACK. Nothing complicated, but the client side code could look a bit messy:

class ServiceA {

func send(completion: (Model) -> Void, error: (Error) -> Void) { /* TODO */ }

func ack(model: Model, completion: () -> Void, error: (Error) -> Void) { /* TODO */}

func trigger() {

send(completion: { [weak self] (model) in

self?.ack(model: model, completion: {

/*TODO*/

}, error: { (error) in

/*TODO Error handling 🙄 */

})

}) { (error) in

/*TODO Error handling 🙄 */

}

}

}

Ok, maybe we don’t need two completion handlers, we could wrap our response into Result type, (which btw. in Swift 5 will be a part of Standard Library). Now the code could look like that:

class ServiceB {

func send(completion: (Result<Model>) -> Void) {/* Implement me */}

func ack(model: Model, completion: (Result<Model>) -> Void) {/* Implement me */}

func trigger() {

send { [weak self] (result) in

switch result {

case .success(let value):

self?.ack(model: value, completion: { (result) in

switch result {

case .success(_): return /*TODO */

case .failure(_): return /*TODO error handling 🤫 */

}

})

case .failure(_):

/* TODO Error handling */

return

}

}

}

}

Is it really better? The code is cleaner, but we still have two nested switch statements. Of course we could refactor this code a bit and extract the second switch into a new private function:

func trigger() {

send { [weak self] (result) in

switch result {

case .success(let value):

self?.handleAck(model: value)

case .failure(_):

/* TODO Error handling */

return

}

}

}

private func handleAck(model: Model) {

ack(model: model, completion: { (result) in

switch result {

case .success(_): return /*TODO */

case .failure(_): return /*TODO error handling 🤫 */

}

})

}

We got rid of two nested switches, but we have split the logic into two functions which are harder to follow and we still have to handle errors in two places.

It’s not hard to imagine scenario involving 3 or more dependent requests. In Swift 1.0 we had pyramid of doom (of if let’s) and here we would have the same type of ugliness.

A potential solution, could be using NSOperation and NSOperationQueue to represent each Request and ACK sent by the client and introduce dependencies between them. Unfortunately this would require creating two classes and writing some boilerplate code. Something that would definitely be an overkill for such a simple case.

Why not using something battle tested in other languages?

Mature languages like Go, C#, Scala or JavaScript have already solved that problem by offering mechanisms such as await/async or co-routines. Unfortunately Swift is not yet providing any of that and for sure this is one of the most expected features of new Swift version. Chris Lattner has already addressed it in his Swift Concurrency Manifesto but its certain that it will take some time until we can fully enjoy some kind of first-class concurrency model in Swift.

Fortunatelly one may leverage some benefits of await/async in current Swift (i.e. 4.2) version and use pattern called promises. So what the promises are? They describe an object that acts as a wrapper for a result that is not yet delivered, usually because the computation of its value is yet incomplete. There is no standard implementation of promises pattern in Swift, but we could use a 3rd party library or implement a simple promise API from scratch. What’s interesting promises were originally offered as third party libraries in JavaScript too, but later starting from ECMAScript 6 they’ve become a native feature of language itself and together with await/async they offer a first-class concurrency model. This has encouraged me to start incorporating 3rd party promises in Swift code as the code using promises is easier to migrate to await/async mechanism.

So how our code with promises could look like?

class ServiceD {

func send() -> Promise<Model> {

/* Implement me */

return Promise(value: Model())

}

func ack(model: Model) -> Promise<Void> {

/* Implement me */

return Promise()

}

func trigger() {

send().then { [weak self] (model) in

return self?.ack(model: model)

}.then { (_) in

/*TODO Implement success */

}.catch { (error) in

/* TODO Implement error handling 🤫 */

}

}

}

Each requests is wrapped with an object of a Promise type that will either deliver some data or fail. Each Promise provides at least two methods then() and catch().

With the first one we provide a closure that is triggered when operation is successful, second one is used to provide a closure for error handling. The then() method can return another Promise so that we can chain promises and catch the error in one place.

Note, that I used a 3rd party promises library written by Soroush Khanlou. Promises are often described together with Futures. Usually a Promise gets constructed and then it is returned as a Future, to be used to extract information when available. The difference is that a Future is a read-only container for a result that does not yet exist, while a Promise can be written. Promises can exist without Futures and for the sake of simplicity I decided to base my examples only on promises.

What are the benefits?

- We have neat chaining and handling of asynchronous operations

- There is a single place for error handling

- Code can be easier transformed when await/async is supported in Swift

So this is a sneak peek of how await/async could look like in Swift?

func trigger() async {

try {

let model = await send()

await ack(model: model)

} catch { (error) in

/* TODO Implement error handling 🤫 */

}

}

Of course it will not work, but the idea is copied from Chris Lattner’s Swift Concurrency Manifesto and syntax is very similar to one from JavaScript. In this approach, each asynchronous function is “annotated” with async keywoard. Then() method from Promise API is replaced with await, that simply blocks invocation until result is resolved. Errors are treated as exceptions and are handled in a standard catch block. Isn’t it nice? Before this becomes a reality we can start using Promises and leverage a bit better asynchronous code handling.